Given 3 months to live, Stella delights in the moment.

Appearing in the Toronto Star Saturday through Monday, Stella's story will be available in three parts on thestar.com. A completely different approach is also available as an eRead, titled Stella, which offers Porter's multi-month diary as she follows Stella, her parents and community. Stella is a compelling read and is available at stardispatches.com now.

Stella Joy Bruner-Methven sits on her favourite couch with her two mothers on a bright October morning and helps plan her funeral.

She is 2.

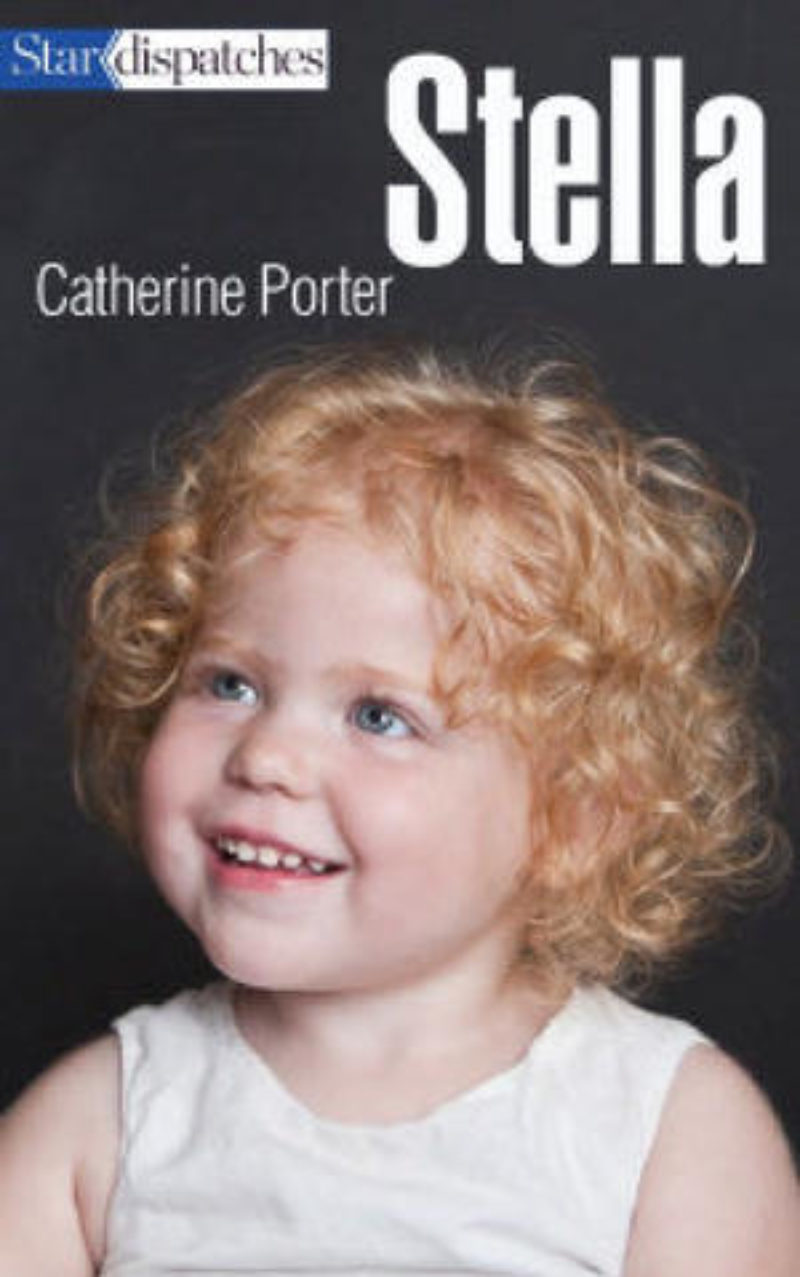

Her loose orange curls catch the soft light filtering through the living room’s lead-pane windows. Her nails are painted apple green, to match her frilly shirt.

She’s been groggy for the past two weeks, sleeping for long stretches and suffering seizures. She stopped breathing two nights ago for seven seconds and her mommies thought she was gone.

But, here she is, alert as a ferret, sitting erect and staring widely at the pretty woman with the shiny lips and big binder talking to her mothers about her upcoming death.

Stella was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumour and given three months to live. That was 3 1/2 months ago, in June 2011.

She is here on stolen time.

“Why did you choose the ‘Salutation to the Dawn’ as the first reading?” asks the pretty lady, a “life-cycle celebrant” named Linda Stuart.

“I grew up at camp, I always wanted Stellie to go to camp,” says her mother Aimee Bruner, tears brimming in her eyes. “It’s a little bit ‘seize the day,’ which is pretty important to us now.”

What about this other poem by Kahlil Gibran?

Now, Stella’s other mother, Mishi Methven, responds:

“If there is a lesson for us to learn from what we’re going through: our grief is our own. Stella is happy. She loves her life.”

Before she got sick, Stella would never have sat here this long. She’d be drawing on the walls in the kitchen. But the tumour has changed her. It’s made her legs stop working, her hands shake and her head throb. It’s also converted her to cuddles.

While her mothers talk, she strokes their cheeks and grabs their hands.

It’s as if, at 2, she wants to console them.

But the tumour hasn’t doused her fire. She’s still Stella Joy — a starburst of energy. When the conversation gets too boring, she decides it’s time to add her thoughts.

“I’m going . . . say . . . something,” she announces in the halting, creaky-door sound that has become her voice. “I’m . . . going . . . say . . . ‘I’m . . . a . . . piglet.’ ”

She scrunches up her face like her beloved pigs at Riverdale Farm. Then she snorts twice.

Since she burst into a crowded hospital room with a thatch of red curly hair, Stella Joy has been what people politely call a “spirited child.”

Even as a baby, she was bursting with energy and attitude. Her birth mother, Mishi, whom she calls Mama, was never allowed to sit during play dates. She had to bounce Stella, facing outwards.

Stella crawled first among her baby friends, walked first, talked first. She didn’t sit on slides, she dove down them. She didn’t lie on the change table, she bucked. She didn’t wait her turn, she snatched it. She liked to tell people loudly, “I don’t like you.” She set a record at her daycare for incident reports — 27 in 18 months — pushing, biting, clocking her friends and then giggling about it later. She laughed during time-outs.

She particularly loved Three Stooges humour. If you tripped and hit your head on something, she exploded in wide-mouthed giggles, revealing each of her Chiclet teeth.

She even laughed in her sleep, which her parents found endearing.

Stella loved accessories: headbands, scarves, hats, bracelets, necklaces, sunglasses, nail polish. The more the better, and preferably all at the same time. She threw a fit every morning when the daycare workers made her leave her polka-dot purse in her cubby.

At 2, she was exhausting and funny and destined to rule the world.

Her friends’ parents admired and pitied her parents.

Then, in the late spring of last year, her moms noticed a small tremor in her right hand as she ate crunchy cereal one morning. She was walking a little pigeon-toed, too. Mishi blamed it on the cheap sandals Aimee had bought at Zellers. So, she went to the Eaton Centre on a lunch break and dropped $150 on pink Geoxes.

Stella called them her “doctor shoes” because two mornings later, she wore them to visit the Hospital for Sick Children’s emergency department. Her pediatrician was on holiday, so her mothers decided to stop in at 6 a.m. to get her some antibiotics for what they assumed was an inner-ear infection.

They were so sure it was nothing, they each called their offices to say they’d be a half-hour late.

And just like that, their perfect, happy life fell apart.

Stella was admitted. Within the first four hours, she’d seen three specialists. Had she been bitten by a mosquito recently? She was scheduled for an MRI that night.

After midnight, a team of doctors in blue scrubs marched in and woke the family up with devastating news. The words they heard through the fog: inoperable; mass; oncology; malignant.

Mishi fainted and triggered a code blue, with five nurses working on her. Paramedics shuttled her on a stretcher to Toronto General Hospital, across the street.

Aimee, who was five months pregnant, kept a startled Stella from falling off Mishi’s lap. Then she went into machine mode, phoning relatives for help.

Stella was diagnosed with DIPG — diffuse infiltrative pontine glioma — a rare and lethal brain tumour that affects only children. Pediatric oncology doctors consider it the most horrific diagnosis they can make.

While tremendous medical advances over the past 40 years have pushed the survival rate of other childhood cancers to 80 per cent, DIPG still offers no hope.

It kills 90 per cent of its patients within two years, most within 12 months. The other 10 per cent, doctors think, were likely misdiagnosed.

Physicians at the Hospital for Sick Children diagnose two to six children with DIPG every year.

Most arrive at the hospital like Stella — entirely healthy apart from some small, seemingly benign problem such as a squint, a headache or a wobble.

“Then you disclose to them their children will most likely not be alive in one year,” says Dr. Ute Bartels, a pediatric neuro-oncologist and a world expert on DIPG.

Hearing this, most parents go into denial, she says.

How can she be sure after looking at some black and white images of their precious child’s brain?

The only other symptom of DIPG: regular laughter while asleep.

Despite decades of research, doctors still understand very little about DIPG. Here is what they do know: the high-grade tumour emerges only in children, mostly between 5 and 9 years old, but it has killed newborns and teenagers, too. It is not genetic or environmentally caused. Instead, it is triggered by a random DNA malformation. The tumour spreads through the midsection of the brain stem, called the pons, “like a blue drop of dye in a glass of water,” Bartels says. Unlike tumours that form a solid mass, it permeates the pons, so to a naked eye the cancer cells are indistinguishable from healthy cells.

The pons is the brain’s Grand Central Station. It not only houses the cranial nerves for essential functions like breathing, swallowing and regulating the heartbeat, but it is the brain’s central nerve pathway, ushering signals to the body below.

As DIPG saturates it, those nerve pathways are shut down like switches on a central power box. One day the child will no longer be able to walk, another she will no longer be able to sit up or hold up her head, then she will lose her voice and maybe her vision, until finally, the command to the heart is cut and the lights go out.

But until then, Stella’s brain would remain on. This is what makes DIPG especially cruel. It destroys the brain’s ability to command, but not to think and understand what is happening.

While chemotherapy and radiation have managed to restrain other malignant brain tumours, they’ve had no effect on DIPG to date. Even trials of the most toxic, high-dose chemotherapy have not slowed its progress. The tumour, doctors say, is crafty: it changes its DNA to evade the effects of chemotherapy.

The only treatment that has proven slightly effective is six weeks of focal radiation. In most of cases, this stalls the tumour’s growth, granting the child what doctors grimly call a “honeymoon period” of no new symptoms.

On average, that honeymoon lasts six months. Some children get a whole year. But there is no guarantee. Some kids get only a week. One in five children with DIPG get no honeymoon whatsoever, only mild nausea and lethargy.

In every documented case, the honeymoon ends abruptly.

“Once the symptoms recur, we know the children will be dead in three months on average,” Bartels says.

But, since Stella was only 2, radiation posed its own problems. There was no way this wild child would lie still strapped to a table for three minutes while the radiation zapped the tender spot behind her ear. She’d have to be sedated with general anesthesia, which would make her groggy.

So her parents were presented with a horrific gamble: do they risk six weeks of their precious daughter’s still-vibrant life now for a possible few extra months later?

That night, they came to the same decision.

Stella would not get radiation or any other life-prolonging treatment — no shunts, no feeding tubes and a do-not-resuscitate order.

Two days later, when her moms met Dr. Bartels for their formal consultation, they were also joined by Dr. Adam Rapoport — the hospital’s medical director of palliative and bereavement service.

“This was the exact opposite of what I normally get,” Bartels says.

Faced with the death of their children, most parents fight to the very end.

Out of 27 children Bartels diagnosed over six years ending in 2008, only three didn’t get radiation — two because they died before it could be administered. Parents of more than half those children also chose a chemotherapy trial, which usually causes terrible nausea and other side effects.

Aimee and Mishi wanted quality over quantity of life.

They would get no medical honeymoon with Stella. But they would make sure her last days were full of everything a honeymoon promises — love, happiness, delight.

Dr. Bartels told them that without radiation, they could expect Stella to live three months.

For a child, three months is a lifetime.

Stella spent that summer radiantly. Both her mothers took leaves from their work. They delighted in her favourite places — the library, the park, the zoo, Riverdale Farm, where she loved to berate the copper-coloured pigs for not peeing in the potty.

They celebrated her birthday at least once a week. They swam at cottages and met Cookie Monster in Sesame Place, Penn. Before the flight down, Stella got to sit in the copilot’s chair until it was time to buckle up. Then she had to be wrestled up the aisle, screaming: “No! This is my plane! That man is not sharing!”

She had ice cream for breakfast and didn’t have to brush her teeth. She was supposed to move from her crib into her own big-girl bed, but instead, she got to sleep between her mothers. They bought a new, king-sized bed, so Stella and Aimee’s swelling pregnant belly would both fit comfortably.

If she noticed the growing tremor in her hand or the increasing difficulty she had walking, she didn’t let it stop her. Her headaches were kept under control by Advil and Tylenol.

“She thinks she won the life lottery,” Aimee said in August. “She’s never been happier in her life.”

For a parent, three months is a nap.

Aimee and Mishi woke up, and it was over.

Now they are waiting for the worst to happen.

Stella can no longer walk. She can no longer stand up on her own. Last night, she told Aimee she couldn’t lie down by herself.

Stella is rapidly receding down the developmental milestones chart.

Her headaches have worsened, too. She often clutches the hair at the back of her head. She now takes regular doses of morphine and anti-nausea medication to combat the effects of swelling in her brain.

The drugs, the tumour and the hydrocephalus — pressure from cerebrospinal fluid that can’t drain past the tumour — have individually or in combination made her fade. Most of the time now, she is dazed — eyes half-mast and unfocused. She returns to her old fiery self for only a few hours every day.

Even then, all she wants to do is sit on “her” comfy living room couch, wrapped in Mishi’s arms.

Her parents are terrified. It’s one thing to decide to accept death in theory. It’s another to helplessly watch your child die.

To fight a disease with a 100-per-cent mortality rate might be futile, but it seems less painful than facing death straight-on.

Hope is a powerful opiate.

Most parents of children with DIPG hope, till the very end, that theirs might be the first kid who beats this terrible disease.

Mishi and Aimee have a different kind of hope. They hope Stella has a good death.

“If you are going to pray for something,” Mishi often tells strangers who say they are praying for a miracle, “pray she’s peaceful and happy and comfortable till the end.”

But that doesn’t mean they are at peace.

Each morning, they wake up fearful. Will she lose the rest of her speech today? Or will she have a violent seizure and die instantly?

Often, children with DIPG dive off a plateau, going from stable to dead in two weeks.

What they fear most is that she will suffer. They fear the moment she goes blind and is alone in the dark.

“Even when she’s alive, she won’t be herself,” says Aimee, whom Stella calls Mommy. “That’s what I’m dreading the most.”

They fear the box of medications and needles they’ve left unopened in Stella’s bedroom.

Their fear their life without her, when they are no longer Stella’s parents.

“We are grieving something that hasn’t even happened yet,” Aimee says.

When she is alert, they play quiet games on the couch — Mr. Potato Head goes shopping, and nail salon. They read her favourite book, Stella Queen of the Snow, about a little red-haired girl and her brother, Sam. (She thinks it was written about her, especially since Mommy is having a boy soon.) They try their best to be brave, even during conversations like this one:

“Stella, do you know you are going to die?” Mishi asks the morning the life-cycle celebrant is due to come to finish planning Stella’s funeral.

Stella nods her head.

“Does that make you happy or sad?”

Stella answers: “Happy.”

Why?

“Because . . . you’re . . . sad . . . now.”

“You’re going to miss us but you’re going to come visit, right?” says Mishi in a sing-song voice.

“Going . . . come . . . visit . . . Mama,” Stella responds.

“That’s good. Mama is going to miss you too because I love you,” Mishi says. Then, she leans down and kisses Stella on the cheek.

Aimee and Mishi sometimes joke blackly that they were designed for this particular tragedy.

Aimee, 34, is the director of operations at Camp Oochigeas, a summer camp for kids with cancer, and has long known Dr. Bartels and Dr. Rapoport.

Her mother, Marilyn Emery, is the president and chief executive officer of Women’s College Hospital.

They’ve both seen cancer up close. They know it hits indiscriminately. They never assumed their family would be exempt.

Aimee’s best friend from childhood summers is Andrea Warnick. She is a grief counsellor for kids. She has a master’s degree in thanatology — the study of death and dying.

Warnick is passionate about death the way many people are passionate about hockey. Long before Stella’s diagnosis, Aimee and Mishi had been regularly treated to Warnick’s stump speech on how death-phobic we are as a society, how we don’t honour our dead as they do in Africa or Central America, how our culture sees it as a failure versus a natural part of life . . .

When Stella was diagnosed with DIPG, her parents knew more about childhood cancer and death than most of us. They hurdled the denial stage of grief.

Mishi, 32, worked as an administrative assistant for the psychiatric department at St. Michael’s Hospital. Now, she uses many of the drugs her colleagues talk about — antidepressants, anti-anxiety pills, sleep medications.

Stella lives in a little brown brick bungalow in East York. There is a flowering crabapple tree on the small patch of grass out front, and a playhouse her grandfather Noel Methven, whom she calls “Poppa,” built for her out back. Poppa lives with Mishi’s older sister Heather Methven in a bungalow directly across the street. Mishi’s mother, Margaret Mohr, whom Stella calls DeeDee, lives in the house directly behind hers, along with Mishi’s teenage brother, Tristan.

The two houses share a backyard.

Before her diagnosis, Poppa would pick her up most days from daycare and bring her home to her favourite couch, where she’d sit with her Auntie Heather drawing or watching an episode of The Golden Girls. Then, on Saturdays, she’d wake up DeeDee and Uncle Tristan for breakfast and have dinner with her other grandparents. If Mishi had planned an adventure, her cousin Gracie, a year older than her, would always come with her mothers, Auntie Andgie (Andrea Bruner, Aimee’s sister) and Auntie Jula (Julia Gonsalves).

Before DIPG was a recognizable acronym to anyone in her family, Stella was being raised in a village. Since then, the village has grown even larger.

Mornings start like this one, the Tuesday after a brilliantly hot Thanksgiving, when her Poppa arrives at 7 a.m. with a box of chocolate Timbits and a bag of bagels from Tim Hortons. He waits on the couch for his girls to wake up. Then he makes them toast and tea. Since Stella’s diagnosis, it’s become his ritual of comfort.

This morning, he waits 45 minutes before Stella appears on Mishi’s hip, wearing yellow flannel pyjamas and demanding television.

She is followed by Auntie Heather, now eight months pregnant, who has come to check on “my girl.” Five minutes later, Aimee’s mother, Emery — whom Stella calls Tutu — arrives with a Bluetooth plugged into her ear and a bag of toilet paper. She has taken time off work and plans to clean the house today. Then, Auntie Andgie steps into the room in her pyjamas. She slept over last night to handle Stella’s 4 a.m. morphine dose, so her pregnant sister Aimee could sleep.

Next, Warnick and her partner, Emily Hopkins, appear in the living room with their 1-year-old daughter, Tobin. The basement apartment was renovated to accommodate them, and they moved in a couple of weeks ago. Hopkins is a pediatric oncology nurse and is here to help with Stella’s medications as they get more complicated. Warnick is here to ease Mishi and Aimee’s anxiety around Stella’s death.

One of Warnick’s regular talking points is how isolating death is in North America. We’ve outsourced it to funeral homes, so we aren’t comfortable around it anymore. Rather than risk saying something awkward, we switch aisles in a supermarket to avoid a grieving mother.

That’s not the case in Stella’s house. Here, grief is a dish generously shared, like love.

By the time Aimee emerges, eight people are settled around Stella, sipping tea and eating toast.

“If we won the lottery, obscenely, this is what we’d do,” says Aimee.

Fortunately, money has not been an issue. Mishi started a blog about Stella and the family’s dark journey. Between readers sending them money and three fundraisers friends and neighbours have hosted, they’ve so far raised $26,000 so that they can afford to stay home. Other unexpected gifts from strangers keep arriving: offers of free family photo shoots, tickets to Canada’s Wonderland, hand-knit blankets and framed portraits of their daughter.

They are not alone in their grief. But Stella’s diagnosis has stripped them of the banalities of play dates and errands that gauze most parents’ days. Their fear has reduced them to their naked selves. And they are very different people.

They met at a group home they both worked at — Mishi as an administrator, Aimee as a social worker. They tumbled into love and were married six years ago in Tutu’s backyard. They both wore long white wedding gowns.

At her core, Mishi is a cerebral introvert. She’s always suffered from that feeling of not quite fitting in. She’s never been good at small talk. But now, she finds even questions like “How are you?” unbearable..

She calls herself a control freak. She needs to know everything about DIPG, and spends hours reading about it on the Internet. She is frustrated by the uncertainty of Stella’s decline.

Aimee, by contrast, is a camp counsellor. She loves people and chaos. She doesn’t analyze. She sinks into the present and can ignore tomorrow. Since the diagnosis, she hasn’t done a single Internet search on DIPG.

Those differences crystallize around the birth of their second child, a boy whom Stella has named Sam, who is due in 11 days. While Mishi gave birth to Stella, Aimee is carrying Sam. Both children were made with sperm from the same donor.

The uncertainty of his arrival pushes Mishi’s anxiety to a new level. Will Stella be dead by the time he arrives? What if they miss one another by a single day?

Mishi can’t cope with two unpredictables. She wants Aimee to be induced a week early.

Aimee feels their children already have a relationship. Stella talks to Sam and touches him through Aimee’s skin. She wants to go into labour naturally, and half of medically induced labours end in Caesarian sections. She worries that after a C-section, she won’t be able to hold Stella or Sam.

The couple compromises. Sam will be induced three days early. The irony: while the family has chosen a natural death, they will have a very medicalized birth.

This Tuesday morning, they have an appointment with their midwife. Stella comes with them at the last minute, her bare feet hanging down from Mishi’s front carrier.

For most of the appointment, Stella zones out, her mouth hanging open, her eyes half-closed behind a pair of purple sunglasses. But when midwife Christie Kavaratzis runs her hands over Aimee’s swollen belly to check Sam’s position, Stella snaps to attention.

“Naaahhh . . . Top . . . Please . . . dan . . . hurt . . . Mommy,” she says. “I . . . don’t . . . like . . . her . . . pushing . . . Sam.”

Sam looks fine. So the discussion, as it always does, refocuses on Stella.

“I’m so nervous I won’t be able to be there for the birth,” Mishi says. “On a day like yesterday, I wouldn’t be able to do anything.”

“We’ll get you there,” Aimee reassures her.

Kavaratzis has become part of Stella’s village. She regularly drops by impromptu. She worries about them daily. Three years ago, at five months pregnant, she suffered a gruesome miscarriage. The tragedy, she says, rocked her marriage. She is awestruck by Aimee and Mishi’s strength and their love for one another.

As a midwife, Kavaratzis normally advocates as little medical intervention as possible. But this is not a normal birth.

She supports Aimee and Mishi’s decision to induce early, but warns them that nature sometimes can’t be tricked.

“Your body might not let you go through with labour in this very stressful situation,” she says. “Part of labour is letting go, releasing and relaxing.”

Stella rouses again for the family’s exit. She cradles her shaky arms around herself and smacks her lips together for Kavaratzis. That’s her newest trademark move: a hug and a kiss. That the old Stella would never have kissed or hugged anyone makes it all the more heartbreaking.

After the family has gone, Kavaratzis walks back into her office, sits downs and worries some more. “I hope they are okay,” she says. “I hope they survive this.”

Sam arrives nine mornings later during a huge fall thunderstorm that smashes electrical wires and trees around town — including a large branch of Stella’s crabapple tree.

When his heart rate plummets for three long minutes, Sam is going to be dug out by scalpel. In the end, he emerges the old-fashioned way, and is greeted by two crying mothers and a room bursting with relatives.

Mishi is there for most of the labour, but suffers a panic attack after his birth and rushes home in tears.

Incredibly, Aunt Heather’s contractions started the same night and she’s still in labour on the same hospital floor, just two doors down.

Stella stayed at home with Auntie Jula.

The next morning, Julia calls to announce that she is walking with Stella to the hospital.

The room goes quiet. It feels like a church, waiting for the bride.

“I never really thought they would meet,” says Aimee.

When she arrives, Stella doesn’t look sick. Her face is bright. Her hair is luminous. Her blue eyes sparkle. She smiles widely.

She wants to hold her baby brother.

Her hands shake and she reaches down to hug him.

“You’re such a good big sister,” Aimee says. “I have two babies, right?”

Later that afternoon, Mishi is back at the hospital for Heather’s birth. She huddles in the hall by a window with her mother, brother and Tutu.

They run their hands over her back, shoulders and hair.

“I had convinced myself I was really okay with this,” Mishi sobs. “I’m not okay. When I came home from the hospital, she smiled at me and I just wanted to die. How will I watch one child decline into death and try to love another child?”

Sam’s birth has shot her back to the moment of Stella’s diagnosis. Grief grips her body.

She describes it like this: a stabbing in her chest; freezing-cold extremities; weak arms and legs; a muscular, mucous ball in her throat.

“I feel like screaming in the night, ‘Don’t you know how special she is? How can you take her away from me?’” she says. “I want to walk off a bridge. That’s how I felt in the first two weeks. I’m shocked that I’m back here.”

A month passes since Sam’s birth. It’s November. The crabapple tree is naked, awaiting winter.

Despite all predictions, Stella is still here.

The family had another scare last week. Stella’s morphine dose was upped again to combat her headaches. She slept almost straight through the next four days. Her colour went grey. The family went into vigil mode. Stella’s Nanny Sandy cancelled a trip to Las Vegas.

Then, on day five, Stella’s light flicked back on. She woke up, smiled, came to the dinner table and ate barbecued steak.

Two days later, she’s back on the couch, either sleeping or like this: eyes wide but rolling. She opens and closes her mouth silently, like a fish.

She can still speak, but barely. Her words arrive in a whisper, 10 painful seconds apart. Just this past summer, Stella was stringing new words together in longer and longer sentences. Now, the tumour is snatching them from her by strangling the nerve that controls her vocal cords.

She is wearing a pair of new, pink Dora pyjamas to fit her lengthening frame. Stella might be dying, but she is still growing.

Mishi is exhausted. She paced herself for three dreadful months.

Stella has lived five months now, and the worst is still coming.

“You never wish your child dead,” Mishi says. “But you wish it is over. You can’t move forwards or backwards.”

Mishi is stuck in death’s waiting room. Her face is wet with tears as she describes the past week to Dr. Kevin Bezanson, Stella’s palliative care doctor.

“It sounds like there are still moments of goodness, although they are fewer and further apart,” Bezanson says from the loveseat across from Stella’s couch. He cycles here every week and carries his stethoscope and laptop in a pannier adorned with an “I am a pinko cyclist” button. He starts every visit by playing with Stella.

“You really have to hold on to those moments.”

Regular doctors speak the language of cures. Bezanson talks about quality of life.

His aim is to help Stella and her family enjoy their last days together. That sometimes means morphine. But it also means regular doses of philosophy.

Stella doesn’t seem to be in pain when she is asleep. She’s comfortable in her mothers’ arms. And when she is alert, she is happy.

She still has life. Her family now has to learn to live it with her, in spurts. They also have to learn how to live with death, not wait for it.

Instead of focusing on the language Stella has lost, she can work with what she still has — yes and no.

“You’d be amazed at how much information you can get out of yes and no,” says Bezanson, 40. “As I said to you in the very beginning, I can’t promise this isn’t going to be hard.”

If Stella’s condition changes over months, Bezanson says, she has months to live. If she deteriorates by the week, she has weeks left. If she changes by the day, her death is imminent.

That’s death’s general road map. But Stella’s condition is rare, and her family’s decision against radiation even more so. Then, there is her fiery personality. She was unmappable in health, perhaps she will be unmappable in death.

Will she be here for Christmas, Mishi demands.

“I don’t know,” Bezanson says.

“I don’t know either,” Mishi says.

From the outside, Stella’s bungalow looks like a happy, wrapped Christmas package on this chilly December night. Through the fogged-up lead-paned windows, the Christmas tree lights glow and dance. You can see shadows of family and friends, all bustling around.

Inside, the atmosphere is bursting with joy. Brad Needham, a friend of the family from Waterloo, is playing his guitar in the corner while his roast cooks in the oven over root vegetables, infusing the room with the smell of rosemary and red wine. He stomps his pink croc in time to the beat of Stella’s newest favourite song — an adaptation of “Oh! Susanna” that goes: “Gracie, Sam and Stella, don’t you cry for me/I come from Alabama with a guitar on my knee.”

Gracie is Stella’s cousin and best friend. She is 3 — a year older than Stella. But today, given Stella’s condition, she seems 10 years older.

She pogos in the middle of the floor. Sam, now 2 months, bounces on Mishi’s lap on the couch.

Our little girl dances in Aimee’s lap in her own way — shaking her head from side to side in time with the beat.

She is wearing a dress covered in red poppies. Her symptoms are more or less the same, but the house is different. Her mothers — Mishi in particular — have changed.

Mishi has been out shopping in the Distillery District with Sam, leaving Stella at home. Two days ago, the family went to buy its first-ever live Christmas tree, a balsam fir, which Stella touched and smelled with them.

Tonight, they’re hosting an ornament-hanging party.

Time is an amazing thing — it gallops along predictably and does unpredictable things. In this case, it has slowly bonded Mishi to Sam and inured her to Stella’s death, one cold step at a time.

“I’ve come to a place of acceptance,” she says. “I can’t stop living, spending 24 hours on the couch, because I lose who I am. One day Stella will be gone and I’ll be still here. I feel more like myself when I’m out doing stuff. I thought I’d be incapable of celebrating Christmas here. I’m surprised. I’m still finding joy in it.”

Instead of seeing each day as the possible day of Stella’s death, she has started to see each one as a possible day of Stella’s life. Her latest mantra is, “Not right now.”

As a clear sign of the transformation, Warnick and Hopkins have moved back to their own apartment. Their help might still be needed, but not right now.

Stella looks like an antique doll, her eyes wide and unblinking, her skin pale. Aimee carries her over to the dining room table, which is covered with ornaments. There is a star with her chubby baby photo in it from her first Christmas, and a new one ornament, featuring four stockings over a fireplace.

“Which one do you want to put up?” Aimee asks her, picking up a little ceramic Starbucks coffee cup. “Mommy’s coffee?”

Stella holds it with a shaky hand and brings it to her mouth, pretending to drink.

While Aimee hangs the ornament, Gracie clambers up on the arms of the couch and quickly hangs another. Looking at them together, you think: life is so random, life is so unfair, embrace life’s gifts now because it might break you tomorrow.

The third song Needham sings is “Wavin’ Flag” by K’naan.

While Gracie bounces in the middle of the room, Stella waves her right hand over her head from side to side from Aimee’s lap. Her fingers are so stiff, they seem to bend backward, double-jointed.

Everyone else follows suit, waving their hands in the air, exhilarated to see Stella engaged. They are here for Stella. They are here for each other. The two have become intertwined.

Catherine Porter can be reached at cporter@thestar.ca